by Derek Bruff, visiting associate director

Earlier this week, CETL and AIG hosted a discussion among UM faculty and other instructors about teaching and AI this fall semester. We wanted to know what was working when it came to policies and assignments that responded to generative AI technologies like ChatGPT, Google Bard, Midjourney, DALL-E, and more. We were also interested in hearing what wasn’t working, as well as questions and concerns that the university community had about teaching and AI.

Earlier this week, CETL and AIG hosted a discussion among UM faculty and other instructors about teaching and AI this fall semester. We wanted to know what was working when it came to policies and assignments that responded to generative AI technologies like ChatGPT, Google Bard, Midjourney, DALL-E, and more. We were also interested in hearing what wasn’t working, as well as questions and concerns that the university community had about teaching and AI.

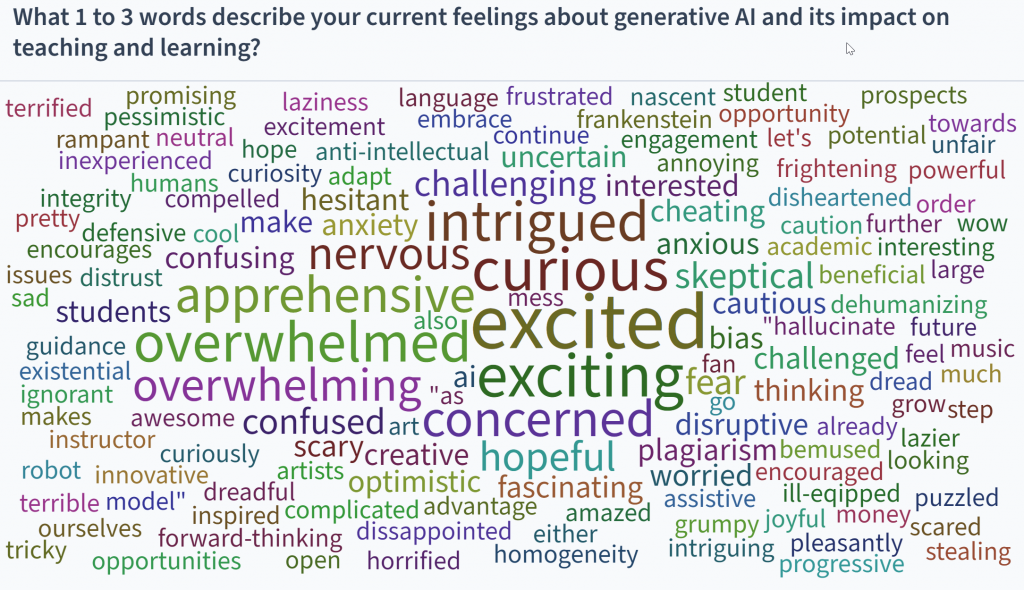

We started the session with a Zoom poll asking participants what kinds of AI policies they had this fall in their courses. There were very few “red lights,” that is, instructors who prohibited generative AI in their courses and assignments. There were far more “yellow lights” who permitted AI use with some limitations. We had some “green lights” in the room, who were all in on AI, and a fair number of “flashing lights” who were still figuring out their AI policies!

Robert Cummings and I had invited a few faculty to serve as lead discussants at the event. Here is some of what they said about their approaches to AI this fall:

- Guy Krueger, senior lecture in writing and rhetoric, described himself as a “green light.” He encourages his writing students to use AI text generators like ChatGPT in their writing, perhaps as ways to get started on a piece of writing, ways to get additional ideas and perspectives on a topic, or tools for polishing their writing. Guy said that he’s most interested in the rhetorical choices that his students are making, and that the use of AI, along with some reflection by his students, generated good conversations about those rhetorical choices. He mentioned that students who receive feedback on their writing from an instructor often feel obligated to follow that feedback, but they’re more likely to say “no, thanks” to feedback from a chatbot, leading to perhaps more intentional decisions as writers. (I thought that was an interesting insight!)

- Deborah Mower, associate professor of philosophy, said she was a “red light.” She said that with generative AI changing so rapidly, she didn’t feel the time was right to guide students effectively in their use or non-use of these tools. She’s also teaching a graduate level course in her department this fall, and she feels that they need to attend to traditional methods of research and writing in their discipline. Next semester, she’ll be teaching an undergraduate course with semester-long, scaffolded projects on topics in which her students are invested, and she’s planning in that course to have them use some AI tools here and there, perhaps by writing something without AI first and then revising that piece with AI input. (It sounds like she’s planning the kinds of authentic assignments that will minimize students’ use of AI to shortcut their own learning.)

- Melody Xiong, instructor of computer and information science, is a “yellow” light in the 100-, 200-, and 400-level courses she’s teaching this fall. She teaches computer programming, and while she doesn’t want students to just copy AI output for their assignments, she is okay with students using AI tools as aids in writing code, much like they would have used other aids before the advent of AI code generators. She and her TAs offer a lot of office hours and her department provides free tutoring, which she hopes reduces the incentive for her students to shortcut the task of learning programming. She also knows that many of her students will face job interviews that have “pop quiz” style coding challenges, so her students know these are skills they need to develop on their own. (External assessments can be a useful forcing function.)

- Brian Young, scholarly communication librarian, and also described himself as a “green light” on AI. In his digital media studies courses, generative AI is on the syllabus. One of his goals is to develop his students’ AI literacy, and he does that through assignments that lead students through explorations and critiques of AI. He and his students have talked about the copyright issues with how AI tools are trained, as well as the “cascading biases” that can occur when the biases in the training data (e.g. gender biases in Wikipedia) then show up in the output of AI. One provocative move he made was to have an AI tool write a set of low-stakes reading response questions for his students to answer on Blackboard. When he revealed to his students that he didn’t write those questions himself, that launched a healthy conversation about AI and intellectual labor. (That’s a beautiful way to create a time for telling!)

Following the lead discussants, we opened the conversation to other participants, focusing on what’s working, what’s not, and what questions participants had. What follows are some of my takeaways from that larger conversation.

One faculty participant told the story of a colleague in real estate who is using generative AI to help write real estate listing. This colleague reports saving eight hours a week this way, freeing up time for more direct work with clients. This is the kind of AI use we’re starting to see in a variety of professions, and it has implications for the concepts and skills we teach our students. We might also find that generative AI can save us hours a week in our jobs with some clever prompting!

Several faculty mentioned that students are aware of generative AI technologies like ChatGPT and that many are interested in learning to use them appropriately, often with an eye on that job market when they graduate. Faculty also indicated that many students haven’t really used generative AI technologies to any great extent, so they have a lot to learn about these tools. One counterpoint: Deborah Mower, the “red light,” said that her graduate students have been content not to use AI in their course with her.

Course policies about AI use vary widely across the campus, which makes for a challenging learning landscape for students. I gather that some departments have leanings one way or another (toward red or green lights), but most course policies are determined by individual instructors. This is a point to emphasize to students, that different courses have different policies, because students might assume there’s a blanket policy when there is not.

This inconsistency in policy has led some students to have a fair amount of anxiety about being accused of cheating with AI. As AIG’s Academic Innovation Fellow Marc Watkins keeps reminding us, these generative AI tools are showing up everywhere, including Google Docs and soon Microsoft Word.

Other students have pushed back on “green light” course policies, arguing that they already have solid processes for writing and inserting AI tools into those processes is disruptive. I suspect that’s coming from more advanced students, but it’s an interesting response. And one that I can relate to… I didn’t use any AI to write this blog post, for instance.

A few participants mentioned the challenge of AI use in discussion forum posts. “Responses seemed odd,” one instructor wrote. They mentioned a post that clearly featured the student’s own ideas, but not in the student’s voice. Other instructors described posts that seemed entirely generated by AI without any editing by the student. From previous conversations with faculty, I know that asynchronous online courses, which tend to lean heavily on discussion forums, are particularly challenging to teach in the current environment.

That last point about discussion posts led to many questions from instructors: Where is the line between what’s acceptable and what’s not in terms of academic integrity? How is it possible to determine what’s human-produced and what’s AI-produced? How do you motivate or support students in editing what they get from an AI tool in useful ways? How can you help student develop better discernment for quality writing?

One participant took our conversation in a different direction, noting the ecological impact of the computing power required by AI tools, as well as the ethical issues with the training data gathered from the internet by the developers of AI tools. These are significant issues, and I’m thankful they were brought up during our conversation. To learn about these issues and perhaps explore them with your students, “The Elements of AI Ethics” by communication theorist Per Axbom looks like a good place to start.

Thanks to all who participated in our Zoom conversation earlier this week. We still have a lot of unanswered questions, but I think the conversation provided some potential answers and helped shape those questions usefully. If you teach at UM and would like to talk with someone from CETL about the use of AI in your courses, please reach out. We’re also organizing a student panel on AI and learning on October 10th. You can learn more about this event and register for it here. And if you’d like to sign up for Auburn University’s “Teaching with AI” course, you can request a slot here.

Update: I emailed Guy Krueger, one of our lead discussants, and asked him to expand on his point about students who have trouble starting a piece of writing. His response was instructive, and I received his permission to share it here.

I mentioned that I used to tell students that they don’t need to start with the introduction when writing, that I often start with body paragraphs and they can do the same to get going. And I might still mention that depending on the student; however, since we have been using AI, I have had several students prompt the AI to write an introduction or a few sentences just to give them something to look at beyond the blank screen. Sometimes they keep all or part of what the AI gives them; sometimes they don’t like it and start to re-work it, in effect beginning to write their own introductions.

I try to use a process that ensures students have plenty of material to begin drafting when we get to that stage, but every class seems to have a student or two who say they have real writer’s block. AI has definitely been a valuable tool in breaking through that. Plus, some students who don’t normally have problems getting started still like having some options and even seeing something they don’t like to help point them in a certain direction.